Barbara Heinzen Colby ’42 was a master at keeping secrets and protecting her family.

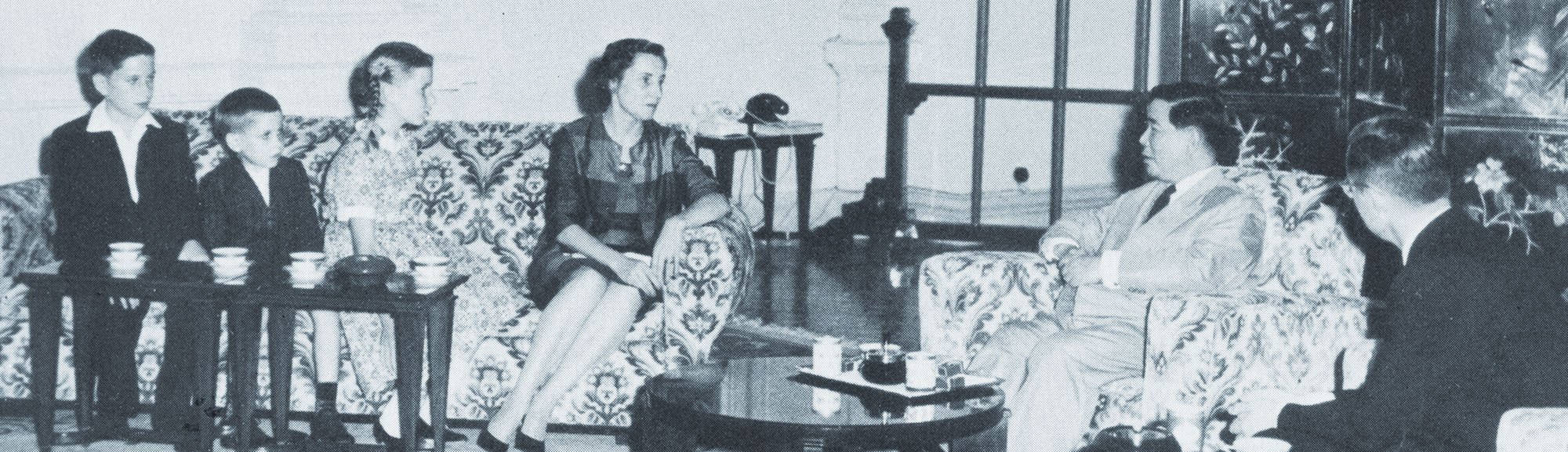

There was the time she turned on the washing machine to drown out her spy husband’s conversations. The many times she hosted parties while pretending to be a diplomat’s wife. And there was the harrowing time when she had to hide with her three children in their home in Saigon during an attempted military coup against their neighbor, South Vietnam’s president Ngo Dinh Diem.

Even though her husband, William E. Colby, was the one actually employed by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) — as an agent and, ultimately, as CIA director from 1973 to 1976 — Colby considered herself a dedicated public servant. She served on the CIA’s Family Advisory Board and in 2022 was honored with a CIA Director’s Award.

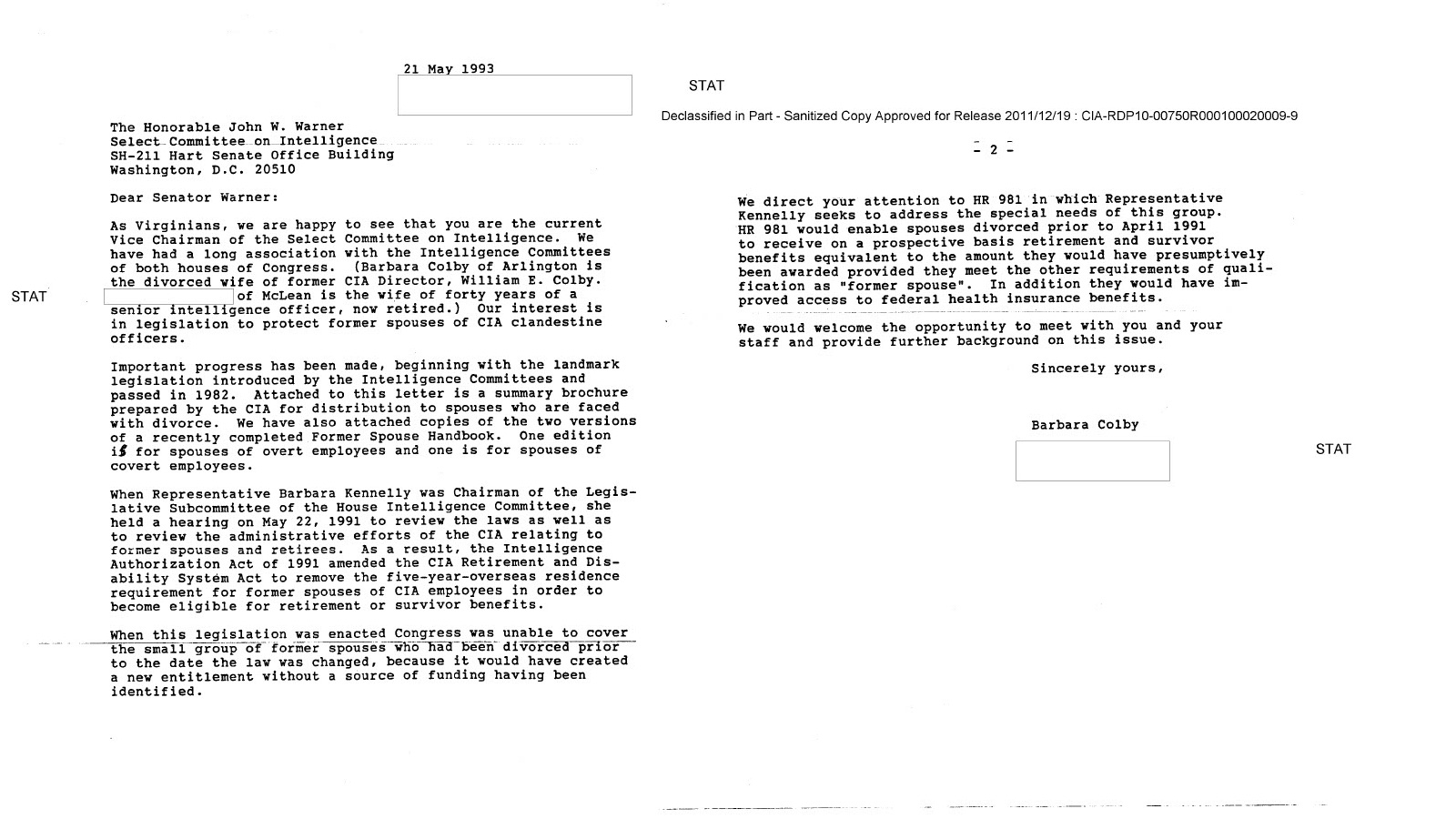

Colby also vigorously campaigned throughout the 1980s for legislation to guarantee lifetime, survivor, and health insurance benefits for former spouses of CIA employees. Before then, these spouses — who were overwhelmingly wives — were often threatened with or faced financial hardships if their marriages dissolved. As loyal partners to their CIA-employed spouses, tasked with living clandestine lives and moving to wherever the U.S. government sent them, they were often unable to build strong social ties or careers themselves.

While preparing for her own divorce in 1984 after nearly 39 years of marriage, Colby was acutely aware of the behind-the-scenes sacrifices she had made over four decades to help maintain her husband’s cover as a spy and the United States’ covert foreign interests and operations.

“During that time, I came to know well hundreds of our wives overseas. … I never ceased to admire the extraordinary devotion shown by these remarkable women in meeting the challenges presented daily to them — in raising their families and in contributing valiant support to their husbands’ assignments in the overseas missions of our government,” Colby wrote in a 1984 statement to the chairman of the Select Committee on Intelligence.

She wrote this statement toward the goal of amending H.R. 5805, the CIA Retirement Act of 1964, to “provide essential benefits” for former spouses where none were previously granted. In 1991, the House of Representatives asked Colby to testify before Congress to speak to the spouse issue, noting that she’d been “a particularly effective advocate.” Even though the bill faced opposition and different iterations, the CIA Spouses’ Retirement Equity Act of 1982 was eventually passed in 1992.

While at Barnard, Colby — born Barbara Ann Heinzen in Springfield, Ohio, on December 25, 1920 — was an active member of the student body. She was elected secretary of the Newman Club, chaired a program in 1940 to welcome transfer students alongside new ones to campus, and led the Interfaith Council to bring together different religious groups in order to increase understanding between them. In 1943, the year after she graduated with a degree in history, Colby was honored with a Bear Pin Award, the College’s highest student leadership award, given to those who exhibit a commitment to more than one on-campus activity during their time at Barnard.

In 1946, she was listed in Barnard’s alumnae magazine as a news editor for the New York State Department of Labor, a year after she became a spy’s spouse. Was the title a cover? It was hard to tell, and she was a challenge to keep up with: She and her family lived in Stockholm (1951-1953), Rome (1953-1958), and by 1959 they were in Saigon.

At age 72, divorced from her spy husband for six years and out of the shadows, Colby completed her master’s degree in the humanities at Georgetown University. In 2014, a year before she died at age 94, the Order of Malta named her a Dame.